Landscape architecture is not what you might think.

Contrary to common belief, it is not “landscaping” or “gardening.” Nor is it horticulture, agriculture, arboriculture or grounds-keeping. It’s something much more. The role of the landscape architect is to design memorable places for people. To fuse together art, engineering and science within both natural and built environments.

The landscape architect lens

A landscape architect views a project through a variety of lenses, assessing existing site conditions and site opportunities as they pertain to user experience.

Reviewing a site’s hardscape environment includes taking a look at all built elements that are either existing, or should be incorporated into a new site design. This includes structures, architecture, walkways, paved areas, retaining walls, stairs, streets and access points, to name a few.

Studying a site’s softscape elements requires taking a larger, more holistic look at the surrounding geography, topography, site flow, drainage, stormwater conveyance, soil types, ecology, wetlands, native vegetation, and horticultural elements.

What ties it all together is how the user experiences and builds a connection with the space. Landscape architects understand that people ultimately drive the design, and that crafting an experience is better than simply filling a void. Well-designed, purpose-built spaces become community hubs—places to gather, connect and interact. They should be inclusive, equitable and engaging for people of all ages and abilities, in all seasons, day or night. This includes a commitment to universal design and full review of and adherence to Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) standards, with a dedication to meet or exceed accessibility.

Design rendering for Ellen Kort Peace Park in Appleton, WI.

Because landscape architects understand how things are constructed, they are able to immediately delve into engineering or architectural drawings and comprehend not just how a space should look and feel, but how it needs to operate as part of the greater environment and as related to both surrounding structure and infrastructure.

Providing for both form and function — “art and smart” — a landscape architect must wear many hats. They must be part engineer or “land-gineer,” — part scientist, part horticulturist, ecologist, planner and artist. They will need to have a strong working knowledge of site planning, stormwater management, environmental restoration, sustainability, planning, resource management, green infrastructure, urban design, soil sciences, botany and fine arts. A landscape architect is familiar with a variety of landscapes and understands native and perennial plants, wetland ecology, riparian systems, trees, soils, erosion patterns and environmental resiliency. They are also acquainted with the historical, archaeological, cultural and social roots of places and create designs to complement, honor and respect.

History of landscape architecture

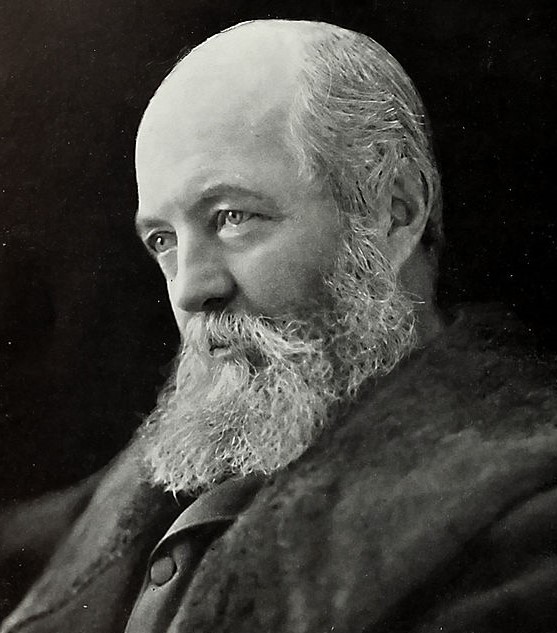

Being a landscape architect may sound like modern-day profession, but it actually dates back to the mid-1800s when Frederick Law Olmsted (or “FLO”) first coined the term. He had just begun designing Central Park in New York City with support from some wealthy friends as a respite for the common people of the city. After serving in the Civil War as the executive secretary of the U.S. Sanitary Commission — the precursor to the Red Cross — he designed many of the most recognized parks in the country. In 1899, FLO’s sons John Charles Olmsted and Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., along with a small group of other landscape architects, created the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA)—an organization that still stands as the premier professional association for landscape architects in the United States, representing more than 15,000 members.

Landscape architecture applications

Landscape architecture is everywhere and involves everything outdoors. It excels in delivering both stand-alone projects such as park and recreation destinations as well as enhancing the environments surrounding existing or new built structures. It can be utilized at the onset of project development to create conceptual designs or renderings—useful in showcasing project possibilities, communicating design options to a community’s leadership and public, or fine-tuning details to meet specific needs, site dimensions, constraints or place-making goals. These designs and renderings can also translate nicely into the development of story maps. Based on the ArcGIS platform, digital story maps can help illustrate project design possibilities through the use of interactive, online maps, videos, project before-and-after imagery and site-specific visuals of concepts, such as in MSA’s ArcGIS StoryMap created for Vilas Park in the City of Madison, Wisconsin. Oftentimes, it is these applications that kick-start the project planning process and evolve into master plans, final designs — and eventually — the finished built product. Coincidentally, the original designer of Vilas Park was a man named O.C. Simonds, one of the founding members of the ASLA. It is his original vision that MSA is working to honor with the updated master planning efforts at the park.

In park and recreation applications, landscape architecture can be seen in the design of parks and green spaces, waterfronts, beaches, marinas, fishing piers, golf courses, public pools, splash pads, athletic complexes, sports fields, multi-use trails, cultural and heritage sites and memorial gardens — public gathering spaces of all shapes and sizes. These types of projects tend to have more of a softscape focus as they work closest with the organic elements of a space: topography, trees, plants, soil, water, sun angles, or wind direction. However, hardscapes play a role as well whenever a project introduces elements such as sidewalks, paved trails, park pavilions, stages, restrooms, concessions, pedestrian bridges, seating areas, retaining walls, electric or lighting. A great example of the blend of hard and soft landscapes can be seen in the transformation of Fireman’s Park in the City of Verona, Wisconsin.

Landscape architectural rendering for Fireman’s Park in Verona, WI.

Incorporating landscape architecture into the built environment means enhancing the spaces surrounding or between existing structures: businesses, civic centers, school campuses, libraries, retail areas, downtown districts, clinics and hospitals, casinos, housing developments, conference centers, business parks, or along transportation corridors. In these scenarios, landscape architecture informs the way buildings are linked together, or experienced as a larger interconnected entity. Designs will take a closer look at traffic and pedestrian flow patterns, public right of way, building entrance and exit areas, parking and loading zones, stormwater conveyance and utilities. Landscape architecture can also be used to help neutralize the impacts of development by creating green spaces, wetland banks, restoration areas, pollinator habitats, or by incorporating trees or plants to help offset the environmental impacts of urban infill or community buildout.

Renderings for the Port of Dubuque, Iowa, waterfront project.

Landscape architecture is also an unexpected companion to more utilitarian engineering and infrastructure projects such as wastewater treatment facilities, lift stations, well houses and stormwater detention basins. In these situations, landscape architects work in tandem with water and wastewater engineers to soften or more seamlessly integrate these systems into their surrounding environments. Some examples might be native plantings or butterfly gardens to accompany stormwater areas, the addition of an interpretive path around a community well house or lift station to describe the buildings’ functions, or the creation of a community park on top of a thoughtfully disguised sanitary sewer overflow tank, as illustrated by just such a project in the heart of Duluth, Minnesota.

The art of possibility

Whether in response to natural or built elements, landscape architecture strives to make every space and every user experience unique. Landscape architects have a keen eye for possibility, turning every stone and peering around every corner to establish potential. Even if a specific use is not identified for a site in the planning phase, the landscape architect will still design with purpose and will seek to create spaces that either speak for themselves or exist in active “conversation” with their surroundings. What many landscape architects strive to convey is that it is about so much more than simply the plants in their plans, but the importance of knitting together and constructing community spaces that benefit users of all ages and abilities in an equitable and exciting way.