The most common refrain at the beginning of a comprehensive plan update process is, “Will this be as long as the last one?” Hopefully not, if we do our jobs well.

City planning dates back millennia, but until about 75 years ago, most city plans were just maps and illustrations — visions of physical form from the minds of architects and landscape architects. Only recently has planning evolved to feature data, community involvement, and thick documents to organize and memorialize it all.

The Comp(rehensive) Plan is intended to promote holistic and strategic thinking grounded in data and backed by community involvement. In theory, the planning process provides data to participants, who then offer informed opinions about public policy, and their involvement helps set those policies and lends legitimacy to the plan. When plan commissioners and council members are faced with tough decisions, they can rely on the plan. That’s how it should work.

In practice, most participants — even those in leadership roles — don’t show interest in the data and don’t have the bandwidth to seriously consider all the policy ideas presented. The effort to consider all the issues means that focus is diluted and the resulting plan fails to capture attention or lead to implementation. In other words, it doesn’t work.

It’s time for a course correction in comprehensive planning: to use less data, fewer words, and shorter policy lists. It’s time for the Lean Comp Plan.

This term is borrowed from the Project for Lean Urbanism, a non-profit that promotes strategies to enable the success of small-scale developers, builders and entrepreneurs. Their Lean Comp Plan Tool is lean itself and worth your time if you work on comprehensive plans. We like many of the policy ideas it offers, including the idea of Pink Zones that strategically reduce barriers to investment.

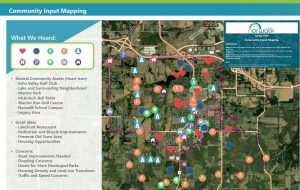

Every planning effort has two major components — a process and a document. Both come with costs, and a community with the will to invest in planning should focus first on the process. A robust engagement effort that genuinely seeks to identify, understand, and incorporate community interests will almost always pay dividends in the form of enhanced public trust in the week-to-week operations of the community.

Document Design

When it comes to the plan document, this is where lean matters. As we like to say among colleagues when we head into a comp plan project, “Be ruthless.” That’s a bit of a joke, but we do encourage the removal of data and the refusal of excess policy ideas. Planners have an affinity for data; we find it interesting and we come up with novel ways to analyze trends and compare communities. But we need to ask the questions of every data point, “What decision does this inform? Can we agree on policies without this information?”

Planners are also trained to present data in tables and graphs, but is this really engaging to the reader? Are they going to need or read all of the data in the table, or the three paragraphs we wrote to explain the table? The current movement is toward creating more visually engaging, graphically designed images and documents that grab the reader’s attention and tell the story without the long commentary.

Process Design

When we turn to the policy making phase, planning processes are built to generate and incorporate ideas. We ask people what they need and what they think, and then we show responsiveness by adding things to the plan — goals, objectives, policies and actions that reflect the good ideas of the many people involved in the process. This makes it “comprehensive,” right? Maybe. But the result is many dozen, sometimes hundreds of ideas spelled out in the plan. This is daunting enough for a large community with more robust resources, and nearly impossible to successfully guide decision-making or drive implementation in smaller communities. The most common refrain at the beginning of a comp plan update processes is, “Will this be as long as the last one?” Hopefully not, if we do our jobs well.

The hardest thing to do in a planning process, and maybe the most important, is to say, “No.” Comp plans need fewer ideas, and the trick is getting there without betraying the principle of responsiveness to community input. The answers are transparency and prioritization. We need to tell people what to expect in the process and we need to consistently ask people not just what they want, but what they want most. It’s easy for someone to say that they support a project, but the decision gets much more difficult when asked to prioritize a number of projects and initiatives. There’s always a trade-off.

Cost

Does “lean” mean “less expensive?” We hear from a community nearly every week that knows they need a comprehensive plan update, and they know they need help to do it, but they’re hoping to spend as little as possible to get it done. The answer on cost is “it depends.” If we’re talking about process and there is limited desire to invest in public engagement, then lean is also cheaper. Planners don’t generally advocate for limited engagement, but we know that we’re competing with things like levy limits and park shelters. If we’re talking about the document — the end result of the process — then lean might or might not be cheaper. Less data means less work, so that’s a start toward less expensive, but great documents are the result of many rounds of editing and refinement, and that’s added expense. If you have a robust stakeholder engagement process and the goal is a lean document, there is probably MORE effort in stakeholder engagement for the prioritization effort. The process of getting down to just the most important ideas adds time and expense.

The case for a Lean Comp Plan is focused mostly on the quality of the plan. Lean should mean more readable and more focused on a smaller number of critical goals and policy ideas. For those communities that want lean to mean less costly too, then lean requires some trust in the knowledge and expertise of professional planners. We can work with some core data and a good conversation with community leaders to assemble a draft plan that fits the community. It’s not “fill in the community name” planning, but it’s also not starting from scratch.

This article was authored by former MSA Senior Planning Team Leader Jason Valerius, AICP, a 19-year employee of the firm.