Imagine if parks, trails, and recreational spaces were designed by children. What would they look like? No doubt, they would be fantastically inventive, interactive, and fun. They might also be a bit different than most adults would expect.

It turns out, ideal natural playscapes in the eyes of children involve climbing, water, obstacles, mud, and a sense of risk which is much more like the woods on the outskirts of town than the plastic playgrounds we often see or think of. Trees, animals, bugs, rocks, dirt – plenty of opportunities to be loud, get dirty and explore. So, why do the majority of our country’s park and recreational spaces consist of tidy, standard equipment on tiny manicured lawns? Interestingly enough, where and when play happens has evolved – perceptions of safety, liability, technology and cost all played a role in shaping modern playgrounds. Because our notion of play has expanded, its importance in the development of children cannot be ignored or kept only as a luxury. All children have a right to play.

Connecting children with nature

When we talk about creating park and recreational spaces that are designed to connect children with the natural world, it doesn’t take much to make the connection. Kids already possess an innate tendency to be more drawn to the natural environment and other biological organisms.

Experiencing the tactile joy of trees.

The same can be said for adults; we have just become further removed from the instinct due to age and societal influence. However we are all, at our core, organic beings with a very basic gravitation to play with other things organic in nature. Research has proven that interacting with the natural world supports human development intellectually, emotionally, socially, spiritually and physically. It supports creative problem-solving, increases physical stamina and dexterity, improves attention and cognitive abilities, promotes healthy social relations, and reduces stress. It also fosters the development of imagination, expression, and emotional discovery. It’s no surprise that nature therapy is commonly recommended for people with Alzheimer’s, dementia, depression, anxiety, PTSD and other cognitive or physical challenges.

Outdoor spaces for natural play

Outdoor play time for children is much different than time spent indoors. Sensory experiences are heightened, and different standards of play apply, such as realizing greater freedom of movement, volume of voice and the ability to get dirty. In addition, children tend to experience nature not as a background to other events, but as the event itself–an interactive, experiential, activity-driven foray into time and space. This tactile experience has no true modern substitute, and all of the best manufactured playground equipment in the world cannot replicate what nature has to offer.

Outdoor education can be either formal or informal, and many schools are now incorporating nature-based play into their standard curriculum. Naturalized outdoor learning environments (OLEs) such as outdoor classrooms and discovery centers are becoming more popular, recognized for their unique ability to teach what the textbook cannot. Yet, these environments also work in great synchronicity with indoor classroom programs, and the tandem approach allows the outdoor space to become part of the learning environment, rather than a retreat from it.

The design of outdoor learning spaces — including those more formally recognized and park and recreational facilities — should incorporate as many varying shapes and tactilely-diverse options as possible, ideally made of natural materials. Logs, stumps, and boulders, paired with trees, berms and the natural rises and falls of topography make for the perfect “built” structural base. Water, vegetation, animals, loose rocks, sand, and a variety of colors and textures fill in the gaps and provide children with places to interact. Designers and educators should incorporate places and features to sit in, under, lean against and provide shelter and shade, with different levels and nooks and crannies for those who seek privacy or quiet.

Inclusive, equitable, universal design

Parks and recreational spaces reflect and represent the heart of a community. As public gathering places, it is their responsibility to be fully accessible, equitable and universally welcoming. For park designers, there are standards of compliance in place to ensure public spaces meet Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requirements. However, park designers can expand upon that baseline to create spaces that also cater to human sensitivities, spectrum disorders, and cognitive, emotional, or sensory challenges. Anxiety, Attention Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorders, people with autism, sight or hearing impairments are all examples. This broader, all-inclusive approach is called Universal Design–a concept first developed by Architect Ron Mace in 1985. Mace defines Universal Design as “the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design.” Universal and inclusive design methodology places attention on the elements of social inclusion, functional use zones, setting and user types, offers opportunities for all ages and abilities, and provides perceptions of safety–the ability to have free play without close supervision.

Playful pathways

The beauty of natural play — and the joy in designing for children — is that even the smallest of spaces holds great possibility and potential for exploration. Not all projects need to be large to be impactful. The creative design of a neighborhood path or trail, for instance, can deliver just as much interactive and imaginative response without taking up as much space, or needing as large of a budget.

This type of localized, smaller-scale play comes naturally for kids, who gravitate toward their own backyard opportunities in vacant city lots and nearby patches of woodland. As urban centers continue to sprawl and infill development gobbles up much of our country’s open spaces, establishing micro-parks, safe pathway networks or “play pockets” in communities of all sizes becomes increasingly important. To a small child, even a sidewalk or a short path through the woods can be an entirely different world: a racetrack, a flowing river, a journey to a distant land where anything is possible. Slight modifications can transform even the most urban environment into something that evokes adventure. Incorporating places to sit, building in curves and textures, planting vegetation, places of sun and shade – all of this encourages movement and spontaneous play, which is essential to cognitive, physical, social and emotional well-being in children and adults alike.

These types of pathways also serve as critical community connectors. When we talk about pathways, we’re talking about a wide variety of possible infrastructure. Greenways, trails, sidewalks, shared-use paths, connectors that join neighborhoods or serve as safe routes to school, or local networks that connect into larger state, regional or national trail systems. They all matter, and they all offer opportunities for safe, equitable, healthful use.

A sense of place

Beyond the physiological and cognitive benefits of play, there is a different kind of fulfillment that is equally as important–a sense of place. This describes the feeling of belonging we have in the environments in which we interact–the sense that these spaces are ours, that we can return to them and they feel like home. This is equally important to consider in the design of park and recreational spaces.

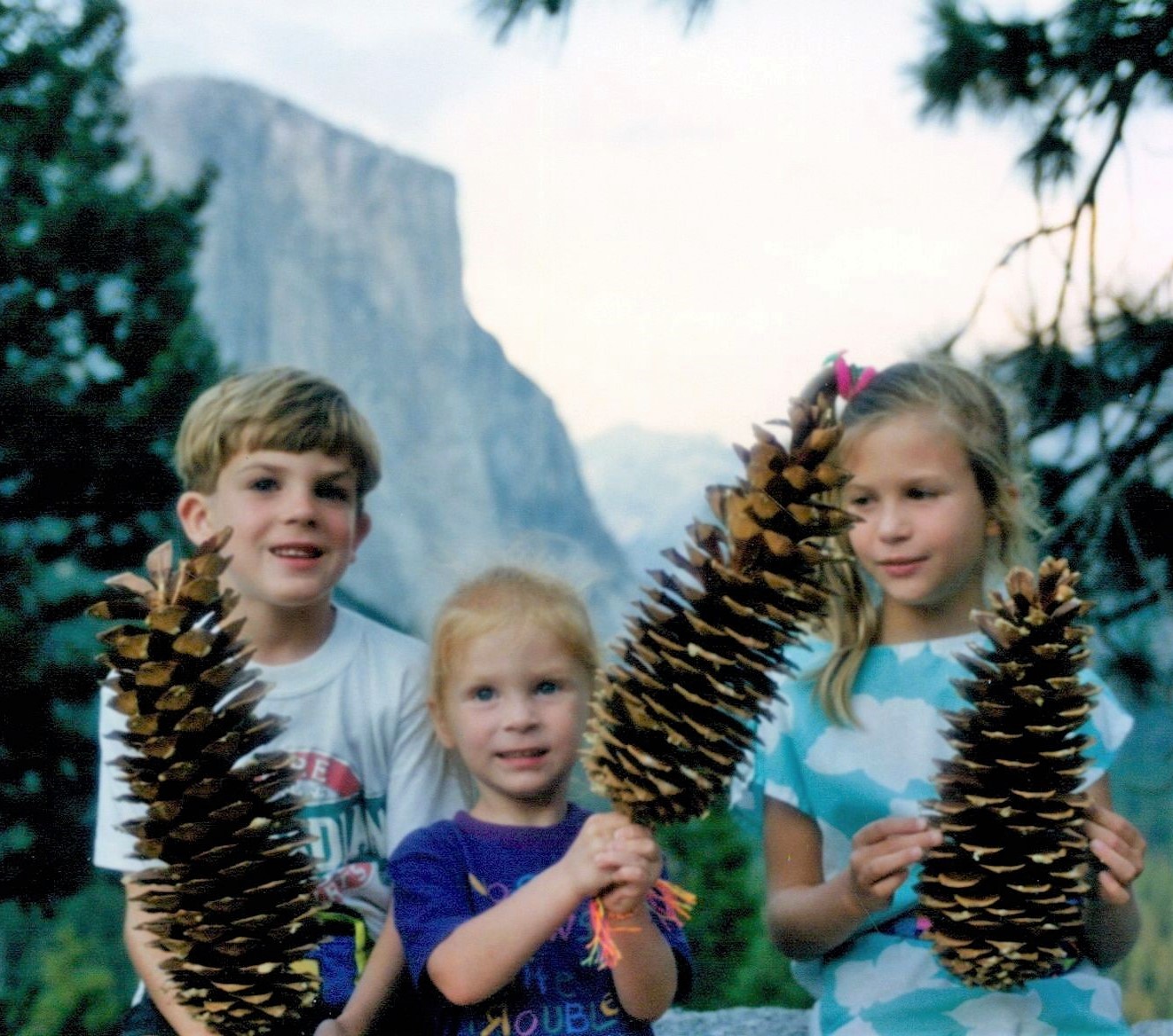

Co-author Shannon Gapp, age 3 (middle), and siblings – discovering Yosemite National Park’s treasures.

A great first step is to create a center or focal point. This should be a highly accessible and visible location. Next, design smaller places of gathering. Some for children only, some for adults or couples, other spaces for large groups or where children and adults can have meaningful interaction and interplay. Ponds, woodlands, meadows, gardens, bridges, shelters, or gazebos are a wonderful start – complemented with rocks, flowers, and places for up-close and big-picture views and exploration. Next, introduce found objects or location markers–unique and identifiable centerpieces that people can meet at, return to, or gauge their direction from. For park settings, creating a center or focal point can also be helpful. After forming the basic spaces and shapes of the landscape, a great next step is to incorporate nooks and crannies. Take a child’s vantage as this is done; look for opportunities to create corners, alcoves, shelves, ledges, hooks, canopies, and cubbies. Create spaces where children can perch, play with small items, be away from the noise and activity of larger groups or secretly stash personal belongings.

Creating playful communities

Play happens outside naturally and numerous studies have illuminated the benefits, perhaps even the necessity, of spending time outdoors for both kids and adults. While it’s unclear exactly how cognitive and mood improvements occur, it is clear that spending time in nature builds confidence, promotes creativity and imagination, teaches responsibility, gets people moving, and improves overall health. Everyone deserves quality places to get outside and play, so we are inviting your community to “play it forward” and help make communities of all shapes and sizes more playful.