Proper stormwater management is critical to protecting community infrastructure, mitigating potential flooding and safeguarding the quality of a region’s water sources. However, construction and maintenance of facilities to safely manage stormwater can be an expensive and long-term investment. As a result, many municipalities are turning to stormwater utility fees as a way to most fairly and transparently share costs.

In the past, communities have relied upon general or street tax funds to pay for needed stormwater system improvements, but many face the bleak reality of infrastructure costs increasing at a faster rate than these funding sources can support.

How does a stormwater utility work?

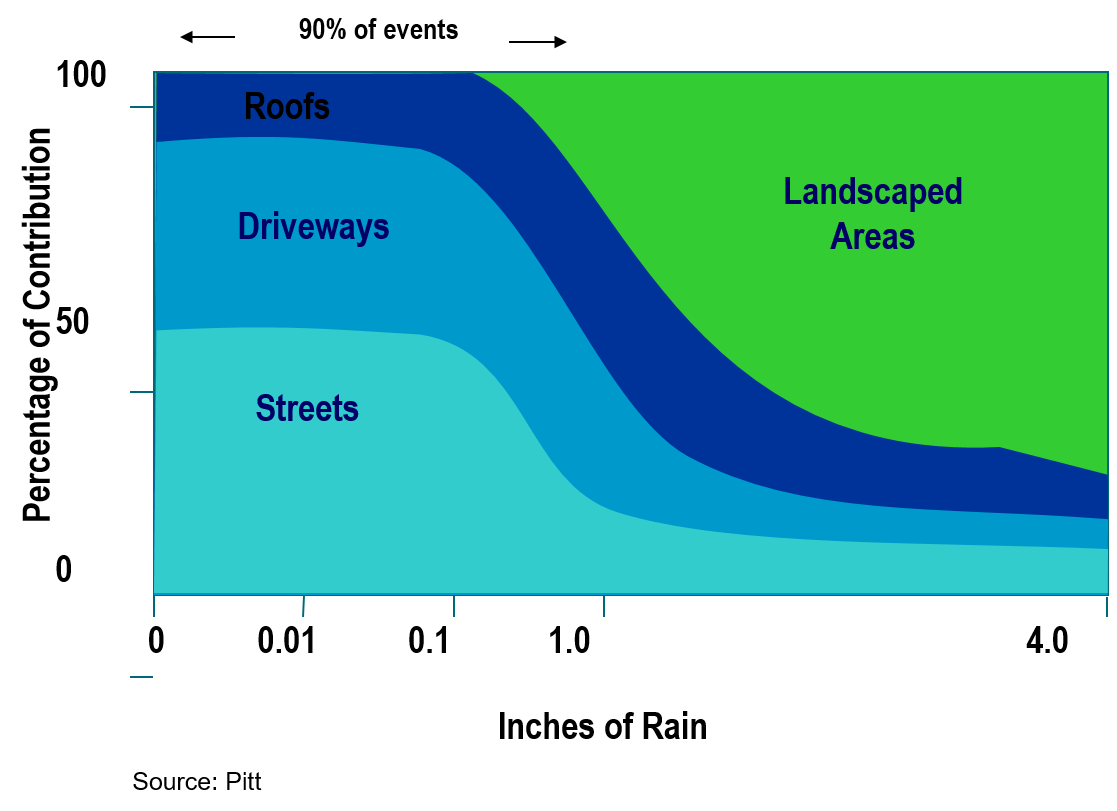

Stormwater utility fees are based on the concept of equitability; specifically, utility charges are based on a fair assessment of the demand that utility customers place on the stormwater management system. In the case of a water utility, customer demand is easily measured through use of water meters. In the case of a stormwater utility, it is stormwater runoff from a site that causes the demand and stormwater runoff can be extremely difficult (and costly) to measure on an individual property scale. It is for this reason that most utilities establish their customer billing systems according to development density. Most commonly, it is the measured amount of impervious area on a property that represents the ‘meter’ for the site. It is a standard engineering principal that as impervious area is added to a property, the amount of stormwater runoff increases; therefore, a site with more impervious area places more demand on the stormwater management system.

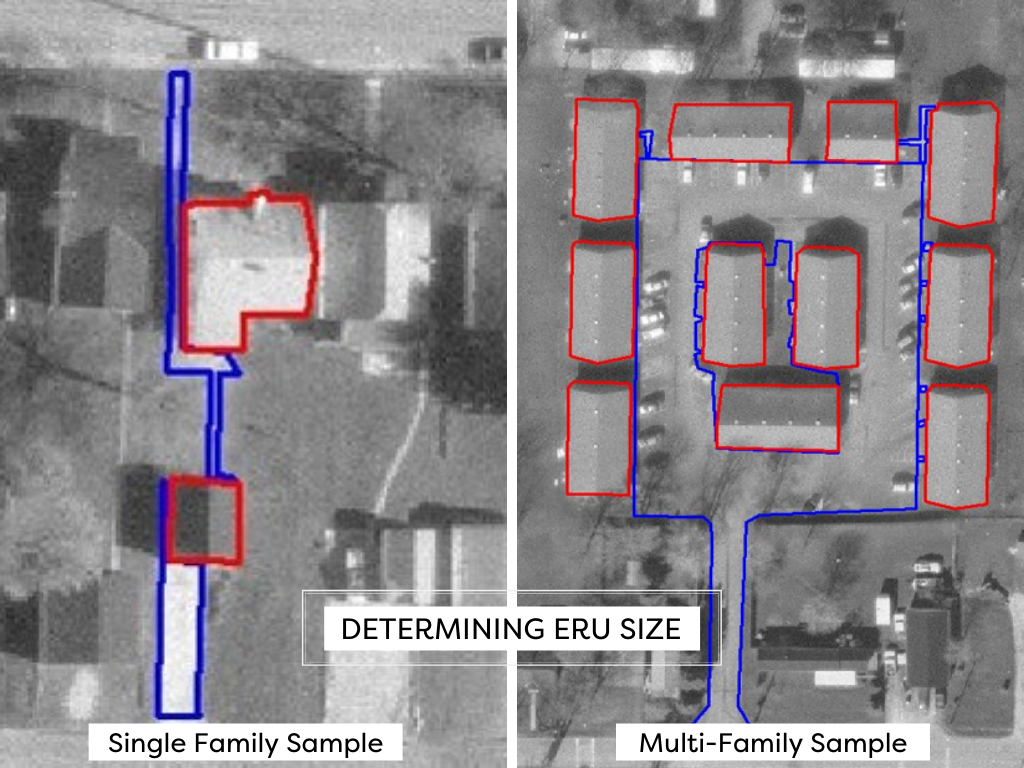

Impervious area is most commonly measured with geographic information systems (GIS), using parcel mapping overlaid on aerial photographs. This is a fairly straightforward process and it can take only a matter of minutes; however, when there are hundreds or thousands of parcels in a community, this can add up to a substantial effort. This effort can be compounded in areas where development is occurring that will require continuous updating of the impervious area measurement.

Note that there are factors which can mitigate this demand, such as stormwater detention ponds which can control a site’s stormwater runoff. These types of considerations are typically applied to utility bills as credits, which serve to reduce the charge that would otherwise be assigned to a parcel.

A common approach which minimizes a lot of the effort in developing a billing database utilizes the equivalent residential unit (ERU) method. An ERU is the average amount of impervious area associated with a typical residential living unit. Generally speaking, under an ERU-based stormwater utility, all single-family residences are charged for one (1) ERU. Non-residential parcel charges are determined based on the measured impervious area relative to the ERU size.

What are the challenges to implementing a stormwater utility?

The short answer is, some customers are often opposed to the introduction of a new fee, period. Developing an educational program to help dispel common misconceptions and demonstrate need will help immensely.

Municipalities will need to consider and clearly state why the stormwater utility is needed. Whether to provide critical flooding/drainage relief or to balance the costs associated with constructing and maintaining necessary stormwater system infrastructure, residents must understand that this is an important long-term investment in their community’s resiliency and success.

Maintaining complete and transparent accounting is also necessary. As the cost of building or repairing public infrastructure continues to increase, contributors deserve to know that a stormwater utility only funds stormwater projects, not streets or other public utilities.

Empowering individuals and businesses to consider ways to reduce use or runoff is also very beneficial. This is where a customer credit program can come into play. Credit programs enable customers to reduce their stormwater charges through a reduction in their usage. While the implementation of a crediting program does reduce the overall utility revenue generation slightly (generally less than five percent), most communities agree it is a minimal concession for greater public support of the program.

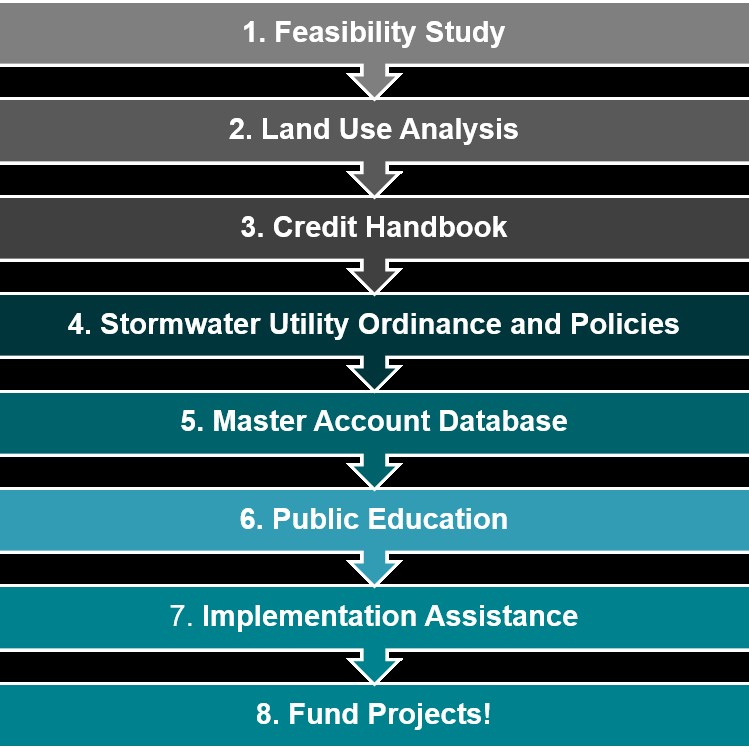

What are the steps toward implementation?

It is helpful to first have a professional feasibility study performed. This study will help define what the proper ERU size is for a community, how many ERUs there are, what the cost distribution will look like and what charge is appropriate to support the stormwater program budget, staffing and operational needs.

Once the feasibility study is complete, a community should consider a more intensive public engagement process, where residents and stakeholders are first educated about the program then invited to play an active role in the decision-making and solution process. Promotion of two-way communication between the city and constituents is the best way to reduce conflict, encourage involvement and gain program support.

Successful case study – Sumner, Iowa

The City of Sumner in northern Iowa is a great example of how a community can implement a stormwater ERU-based utility for the public benefit. The community suffered a catastrophic 100-year flood in 2016 and then was struck by an even more devastating 500-year flood in 2017 that inundated portions of the town and caused significant property damage. The city council determined in the course of recovery efforts that more had to be done to address stormwater issues across the community and reached out to MSA to discuss options. The city worked with MSA to scope flood mitigation solutions and also implement an ERU-based stormwater utility to provide a revenue source for stormwater maintenance and flood mitigation projects.

Much of the city’s storm sewer system was found to be in poor condition and incapable of handling stormwater from large flood events. To improve flood protection in the community, it was determined to focus on regional stormwater detention which would reduce peak flows associated with major rain events.

MSA engineers developed a design that would work within the natural topography of the northeast quadrant of the city and mitigate the 100-year flood risk. The solution was the creation of three separate detention basins spanning over 17 acres and providing approximately 86.4 acre-feet of storage. The basins capture stormwater from an approximately 185-acre watershed. A temporary connection allows the detention basis system to slowly drain into an existing 30” storm sewer that runs under nearby Walnut Street. The basins were constructed in 2020, and design has been completed on permanent discharge from the three-cell stormwater detention basin system using a combination of drainage ditches and box culverts to convey stormwater to the Little Wapsipinicon River.

The creation of the stormwater utility for the City of Sumner proved to be a critical first step in helping to fund a number of essential stormwater improvements across the community, including a portion of the detention basins — a project selected by the American Council of Engineering Companies (ACEC) of Iowa to receive a 2022 Engineering Achievement Award in the category of Special Projects.

When thoughtfully planned and implemented, a stormwater utility system can be a logical solution for successful stormwater management and an equitable means to collectively fund, safeguard and preserve vital community assets and water sources.